Opinion: Israel and Palestine: A way forward

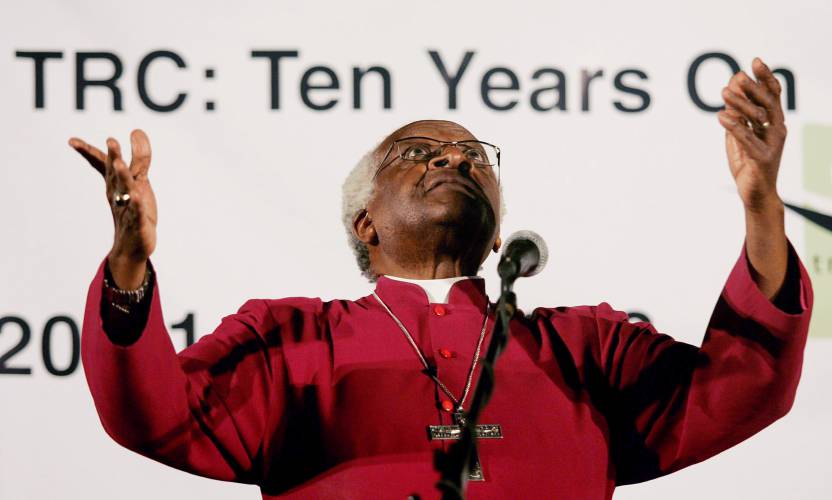

FILE - Former Truth And Reconciliation Commissioner (TRC) Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu gestures during a public debate on the legacy of the TRC in Cape Town, South Africa, on April, 20, 2006. Tutu was a Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and a retired Anglican Archbishop. (AP Photo/Obed Zilwa, File) Obed Zilwa

| Published: 03-15-2025 6:00 AM |

Scott Dickman is a board member of New Hampshire Peace Action and belongs to the Compassionate Listening Project.

On February 20, I co-authored a My Turn advocating for protests against Israel’s occupation of the West Bank by halting U.S. shipments of armaments to Israel.

A friend questioned the argument as ‘one-sided,’ and, yes, the tone and emphasis were deliberate, given the far-reaching consequences of Israeli policy. My reasoning at the time was based on the potential consequences of an Israeli de facto annexation of the Occupied West Bank. An annexation would effectively negate the possibility of an independent Palestinian state, and one could easily foresee the likely escalation of violence and further erosion of any path toward a just and lasting peace.

Responsibility for conflict should not be measured by “body count” but by choices at the highest levels of government either to perpetuate violence or seek peace. Hence, each side is accountable for its actions and its role in either inciting violence or disrupting the cycle of harm. If we seek a path to peace after decades of failed diplomacy and violence, we must acknowledge that leadership on both sides has failed.

A broader narrative is needed, along with a new paradigm, one that recognizes each side’s fears and prioritizes reconciliation over perpetual warfare.

First, however, we must acknowledge that the violence of Oct. 7 and the devastation in Gaza have shattered trust on both sides, leaving trauma so deep that reconciliation may seem impossible. Yet hope must prevail. Painfully, we know the alternative all too well. History offers recent examples, such as South Africa and Northern Ireland, where peace did not emerge from trust but from the recognition that perpetual violence was unsustainable. It also shows how fear, vulnerability and the absence of self-determination fuel conflict.

In the case of Israel and Palestine, Jewish vulnerability arises from centuries of persecution, diaspora, genocide, persistent antisemitism, regional hostilities and existential threats. These experiences have fostered a deep-seated need for security, resilience, and self-determination.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

New Hampshire farmers believed USDA grants were secure bets. Then, federal funding halted.

New Hampshire farmers believed USDA grants were secure bets. Then, federal funding halted.

Merrimack Valley schools to eliminate 21 positions, lay off up to 3 employees

Merrimack Valley schools to eliminate 21 positions, lay off up to 3 employees

Bow residents unhappy with school board’s recording policy, demand more transparency

Bow residents unhappy with school board’s recording policy, demand more transparency

‘Supposed to protect me’: For kids in state custody, NH’s foster care system can lead to placements thousands of miles from home

‘Supposed to protect me’: For kids in state custody, NH’s foster care system can lead to placements thousands of miles from home

A partial solar eclipse will be visible Saturday at sunrise

A partial solar eclipse will be visible Saturday at sunrise

Concord’s John Fabrizio named New Hampshire’s special education administrator of the year

Concord’s John Fabrizio named New Hampshire’s special education administrator of the year

Palestinian vulnerability arises from forced displacement, occupation, statelessness, economic hardship and the denial of self-determination. These conditions have fueled a persistent struggle for rights, identity, dignity and sovereignty amid ongoing conflict and geopolitical instability.

Unsurprisingly, both narratives are shaped by deep intergenerational trauma, and both sides have resorted to violence in the pursuit of safety.

In South Africa and Northern Ireland, when political and military solutions repeatedly failed, a “third way” emerged, one that prioritized understanding and acknowledging the pain and aspirations of the other. The success of reconciliation efforts in these countries affirms that when each side humanizes the other, lasting peace becomes possible.

For example, South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission of 1996 sought to uncover human rights violations, emphasizing forgiveness over retribution. Similarly, the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 ensured all parties in Northern Ireland had a voice, fostering reconciliation. Both efforts relied on compassionate listening, acknowledgment of suffering and structured reconciliation.

A fundamental obstacle to peace is the narrative each side holds of the other. Israelis and Palestinians are taught early on the stories of historical grievances and violence, shaping their identities, reinforcing divisions and justifying continued mistrust. Compassion challenges these narratives by encouraging individuals to listen to the personal experiences of those on the opposing side.

Programs like Combatants for Peace and The Parents Circle-Families Forum bring together Israelis and Palestinians who have directly experienced the consequences of violence. Through dialogue, former soldiers and grieving families recognize their pain mirrored in the other’s experience, grieving and healing together. Compassion allows individuals to meet not as enemies, but as fellow human beings who, like each other, love, suffer and long for peace, hoping for safety, health, access to education, meaningful work and the opportunity to fulfill their potential.

Advocating for compassion and respectful dialogue in this context is challenging. Anger runs deep, and ongoing violence only deepens wounds and fuels cycles of retaliation. Many Israelis fear that showing compassion toward Palestinians threatens their security, while many Palestinians worry that recognizing Israeli suffering undermines their struggle for self-determination. Yet, compassion is essential in shaping political dialogue. When negotiators approach discussions with a genuine understanding of the other’s experience, perspective, and aspirations, policies are more likely to reflect these critical considerations.

Nelson Mandela’s leadership in post-apartheid South Africa is a powerful example of how compassion, rather than vengeance, can heal divisions. If Israeli and Palestinian leaders adopted a similar approach — acknowledging each other’s suffering and seeking solutions that ensure dignity and security for all — a breakthrough in peace efforts could be achievable.

“Kumbaya”? Perhaps.

But regardless of religious affiliation, fundamental moral principles should guide our policies and how we treat each other: with respect, fairness, justice, and compassion. May it be so.

Opinion: What Trump really means by government efficiency

Opinion: What Trump really means by government efficiency Opinion: To salvage democracy, rebuild the Democratic Party

Opinion: To salvage democracy, rebuild the Democratic Party