Forester of the Year knows woodlands are more popular and more endangered than ever

| Published: 03-23-2025 8:44 PM |

It seems pretty clear that Wendy Weisiger the youngster wouldn’t have been too surprised if a time portal had given her a glimpse of Wendy Weisiger the adult at work.

“I was an outdoors kid, and I wanted an outdoors job,” said Weisiger when asked why she grew up to become a forester. In heavily wooded New Hampshire, you can’t be more outdoorsy than that.

Weisinger, who graduated from the University of New Hampshire Forestry Program in 2001, has been a forester at the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests since 2004 and is now its managing forester. She oversees two other foresters and a Christmas tree farmer in maintaining the society’s 200 properties covering 66,000 acres all over the state.

Weisinger was recently named Forester of the Year by the Granite State Division of the Society of American Foresters, a recognition of her “long record of effort, service and accomplishments,” according to Connor Breton, chair of the Granite State Division SAF and forester with the N.H. Division of Forests and Lands. “These are people who lead by example and who show or teach others the good that forestry can do in the places they love. Wendy is highly deserving of the award for these reasons and for many others.”

So what does a forester do, besides cutting down trees? Lots of walking through the woods, measuring, counting and analyzing, often after setting up a grid in a GIS system to help collect data.

“You can only manage a property once you know it,” she said. “That’s what field foresters do, any forester does: take inventory of the property so they can develop management plans, manage boundaries, think about how to best set up our lands.”

“We measure trees, look at wildlife habitat, cultural resources, recreational resources, water resources, we have a bunch of metrics, we develop a management plan to guide what our actions will be on a property over the next 10 to 15 years. Where might we implement timber harvest, mow fields, repair roads, mark our boundaries?” she said. “We look at the forest structure and density and health, and literally outline where we want to take action to change the trajectory of how a forest is growing

“We might say, OK, this forest is all one age and with few types of tree species, with maybe nothing growing underneath. Let’s put in some openings so we can diversity the overall age of forests, different sizes of trees, so we can grow different species of trees,” she said. “That’s the way to set our forest up for success in the future – to be diverse.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

‘Supposed to protect me’: For kids in state custody, NH’s foster care system can lead to placements thousands of miles from home

‘Supposed to protect me’: For kids in state custody, NH’s foster care system can lead to placements thousands of miles from home

Concord’s John Fabrizio named New Hampshire’s special education administrator of the year

Concord’s John Fabrizio named New Hampshire’s special education administrator of the year

New Hampshire farmers believed USDA grants were secure bets. Then, federal funding halted.

New Hampshire farmers believed USDA grants were secure bets. Then, federal funding halted.

Monitor names winter 2024-25 Players of the Season

Monitor names winter 2024-25 Players of the Season

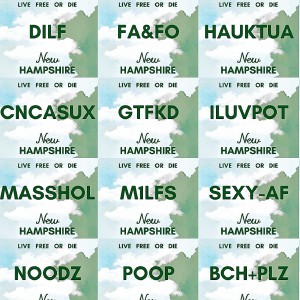

Sunshine Week: Creative and curious, vulgar and offensive – DMV rejected 342 vanity plates in 2024

Sunshine Week: Creative and curious, vulgar and offensive – DMV rejected 342 vanity plates in 2024

Bow residents unhappy with school board’s recording policy, demand more transparency

Bow residents unhappy with school board’s recording policy, demand more transparency

Diversity is important because hovering over everything is climate change, which is altering the conditions under which forests have thrived and forces a rethinking of past practices. It’s no longer possible to sit back and let nature take its course because we have over-ridden nature.

Most New Hampshire forests were cut down within the last century and a half; virtually none are old-growth. Add in pollution, development and invasive species, compounded by changing precipitation, temperature patterns and even the shape and size of seasons, and people have no choice but to manage state woodlands. Making them diverse means they are less likely to be decimated as conditions change.

“We’re on the brink of a climate crisis. More and more the public is focusing attention on our forests both as a place of refuge and for their important role in helping to mitigate the impacts of climate change,” she said.

The pandemic and lockdowns compounded matters, sending thousands of people into the outdoors for the first time. Weisinger said the Forest Society saw the impact of crowds throughout its properties.

“It was great but we were not prepared for that kind of use on our lands and it really has not decreased since then. It’s a good thing but it’s expensive and it takes a lot of resources to manage that,” she said.

And it showed something else: “People really care about forests.”

David Brooks can be reached at dbrooks@cmonitor.com.

Henniker ponders what is a ‘need’ and what is a ‘want’

Henniker ponders what is a ‘need’ and what is a ‘want’ Boscawen residents vote to fund major renovation of public works building

Boscawen residents vote to fund major renovation of public works building ‘Voting our wallets’: Loudon residents vote overwhelmingly against $1.7M bond for new fire truck

‘Voting our wallets’: Loudon residents vote overwhelmingly against $1.7M bond for new fire truck In Pembroke, Education Freedom Accounts draw debate, voters pass budget

In Pembroke, Education Freedom Accounts draw debate, voters pass budget