Sunshine Week: Committees are a pillar of city government. Concord keeps the public at arms length

Images from committee meetings in 2024. At city council and other major meetings, shown bottom right, the city follows different public transparency practices. Catherine McLaughlin / Monitor staff

| Published: 03-21-2025 5:48 PM |

The vast majority of issues taken up by the Concord City Council are first reviewed by one or more of several dozen committees, which make recommendations about city decisions.

Their work spans a range of issues: Should a bus stop be moved for safety reasons? What should the city’s plan to address homelessness look like? Did an elected official have a conflict of interest in a vote?

While “advisory” in nature, these committees shape city programs and how money gets spent. Despite the weight of committee recommendations, the information underpinning them is held at arms-length from the public.

Committee meetings are not recorded or broadcast online the vast majority take place during the workday, making it difficult for working city residents to be present — in the room or at home — for discussions. Meeting materials are not available online, so anyone who couldn’t attend a meeting wouldn’t be able to see the data or reports or renderings that informed a committee’s debate. Voices aren’t amplified through microphones and speakers and members aren’t reminded to speak loudly, making it a challenge for someone who did show up to hear what was said. City staffers who print handouts for committees don’t typically make extra copies for public attendees.

“They’re acting on our behalf,” said Greg Sullivan, president of the New England First Amendment Coalition. “We have a right to know about what’s being said.”

While city leaders have taken a few steps aimed at diversifying the membership on these committees in recent months, many transparency and accessibility practices that the Concord City Council follows don’t extend to its advisory boards.

By contrast, Concord’s major boards — the city council, zoning board and planning board — all meet in council chambers roughly once a month on weeknight evenings. Meetings are recorded, streamed live and posted online. All participants, including the public, have their comments delivered through the room’s audio system for all to hear. Though separate from City Hall, the Concord School Board and its committees operate this way, too.

Attached to each agenda are city reports, communication that’s related to an issue, written public testimony, and memos or presentations considered by the board at the meeting. Members of the public can review, for example, an application before the planning board ahead of time to learn more about it and decide if they’d like to testify, for or against, in a public hearing.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

‘New Hampshire is just going to embarrass itself’: Former Child Advocate warns against proposed office cuts

‘New Hampshire is just going to embarrass itself’: Former Child Advocate warns against proposed office cuts

Two of five Grappone auto franchises to be sold as part of family transition

Two of five Grappone auto franchises to be sold as part of family transition

‘Erosion of civil public discourse’ – Concord mayor makes plea for more civility

‘Erosion of civil public discourse’ – Concord mayor makes plea for more civility

GOP lawmaker wasn’t fired over transgender bathroom comments, business owner says

GOP lawmaker wasn’t fired over transgender bathroom comments, business owner says

‘A large chunk of change’: Feathered Friend Brewing disputes tariff on Canadian import

‘A large chunk of change’: Feathered Friend Brewing disputes tariff on Canadian import

‘It's like slow genocide’: Crowd rallies against proposed Medicaid cuts

‘It's like slow genocide’: Crowd rallies against proposed Medicaid cuts

Whether a minor committee or a major board, “Any government agency,” Sullivan noted, “the rules are the same.”

Even the process for joining committees is veiled. Other than submitting a resume and letter of interest, the process isn’t laid out anywhere. Per the city council’s unwritten process, they won’t vote or discuss in public a nomination until they’ve already determined privately that the person should be on the committee.

When Ward 5 Stacey Brown raised questions in a council meeting about why the city didn’t require resumés for reappointments, she was interrupted by Mayor Byron Champlin, who criticized her for not raising her concern with him privately.

“Councilor, we have a process, which is you saw these nominees last month and if you had objections to a member, that is the time to bring it forward,” he said. “Not bring it forward in a public meeting.”

Michele Horne, the Ward 2 city councilor, campaigned on the issue of increasing diversity of who’s serving in these groups. She’s worked with the city clerk to collect and post a list of all vacant positions on the city website and she is helping the city launch its first unified application portal for those interested, initiatives she said she’s proud of.

More broadly, though, Horne thinks more could be done to make it easy for the public to know what committees do and talk about.

“I’ll put on my social media that something happened or was discussed at a specific meeting last night, and people tend to not know when and where these meetings are, and what’s going to be covered and what might be on the agenda,” she said. “I just wish we had a better system for getting that information out there, so that people didn’t have to just go to the website, look through the 54 different committees, or whatever it is, and try to figure out what’s on the agenda.”

To see how this plays out, here’s a quick look at four committees whose work became of particular public interest in the last year.

The city’s ethics board weighs and, if merited, holds hearings on ethics complaints filed against local officials and makes recommendations to city council about whether or not they should face any discipline.

Before last summer — without any filed complaints to take up — it hadn’t met in twelve years, but three ethics complaints, two of which made claims against city councilors, meant it held a series of meetings from June through September.

Its most recent meeting, which began at 9:30 a.m. on a Monday and was held in the city hall conference room, involved a hearing on a complaint that councilor Brown had a financial conflict of interest on a vote she took. The board determined that Brown had not violated city ethics rules.

While available through public records requests, ethics complaints and any responses submitted by those named in them are not posted to the city’s website or included in the agendas or minutes for meetings where they are discussed.

Members of the board sat face to face at a conference table and spoke softly, making their deliberations at times scarcely audible to those in attendance. This is often true of meetings held in the conference room.

Its next meeting, to consider a recent complaint against several members of the city’s Golf Advisory Committee, will be April 9 at 9:30 a.m. in the same location.

To address what is broadly cited by residents and leaders as one of Concord’s most pressing issues, this steering committee has started meeting more often and is driving the city’s plan to reduce homelessness. It typically convenes at 2:00 p.m. on the third Tuesday of the month at the Chamber of Commerce.

In contrast to most other committees, slides with data reviewed by the committee at meetings have sometimes been attached to minutes, if not to agendas, especially in recent months.

Multiple city residents experiencing homelessness have expressed an interest in attending these meetings, Horne noted, but few have done so. Public attendance was far higher at a meeting the committee held in council chambers last fall.

This ad-hoc committee was assembled to review design options for a new clubhouse at the city’s golf course.

It typically met at 8 a.m. on Thursday mornings in the restaurant at the current clubhouse and was one of three committees — alongside the Golf and Fiscal Policy Advisory Committees — that recommended the city move forward with an $8 million clubhouse rebuild.

The main feature of these meetings last year, presentations showing three design options and their projected costs, were never attached to its agenda or minutes.

To see a copy of the beaver meadow designs, members of the public have to know which dates the city council discussed them, go into city council agendas, then download the presentation from there. They’re not presented anywhere on the city website.

By contrast, another controversial Concord project is the school district’s plan to build a new middle school. That project has a dedicated public information page on the district website that includes nearly every design, memo and presentation the board has reviewed going back to 2017. Its committee and subcommittee meetings on the project were recorded and posted online. Both the school district and the city have a dedicated public information officer.

This committee makes recommendations about how large the city’s tax credits should be for veterans, seniors and people with disabilities.

No agendas for the committee are available online, and a meeting announcement is not posted on the city calendar. It meets at irregular intervals.

The most recent meeting in February was held in the city hall conference room, where discussions were often too quiet to make out.

During the meeting, a resident who attended moved his seat closer to the conference table, straining to hear.

City officials often emphasize — as the mayor recently did regarding the clubhouse project — that these boards largely have advisory roles: they don’t have formal decision-making power.

“The committees do the digging into an issue and then report back to the city council with a recommendation,” Champlin said in an interview.

At the same time, committee recommendations carry significant weight in what city leaders decide to do because of the “digging” they’ve done and because of their background knowledge.

“A lot of the times, the committees are a lot more educated on things than the City Council is, that’s why we refer things” to them, Horne said. “It’s great that you have these well-educated people in very specific areas where someone sitting on the council can’t be educated in safety, and conservation management, and building codes, and other things.”

Being forthright with meeting information not only supports transparency but also participation.

A member of the city’s Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, Justice in Belonging committee recently noted that, for people with certain disabilities, being able to access and go through things like slides or maps in advance of a meeting is essential to their ability to be involved and informed. Notably, video recordings of those meetings have been made but not posted.

The same principle of participation applies to those not on boards.

“Anything a quorum of a committee is seeing is a public record and ought to be provided publicly,” Sullivan said. “Then, at least, people can see what it is they’re talking about.”

Sullivan noted the preamble to the state’s Right to Know law, which entitles the public to “the greatest possible public access to the actions, discussions and records of all public bodies.”

Recording government meetings isn’t required by the law, but it is a best practice, Sullivan said. “The goal is the public knowing what the government is up to to the maximum extent possible.”

The law specifically addresses, and requires, that the audience be able to hear all parts of a public meeting.

RSA 91-A states that “each part of a meeting required to be open to the public shall be audible or otherwise discernable to the public at the location.”

When coming into office last January, Champlin undertook a personal review of the city committees, cutting a few that weren’t required by city code and hadn’t met in some time as well as starting or reviving others, including the diversity and equity committee.

“Accessibility is something that we keep in mind when we schedule for the places we hold committees,” Champlin said. “That’s one of the things that’s important to me is, are they accessible to people with limitations?”

When asked about meeting recording or remote participation, he said “it’s something that we should strive for,” but emphasized that technology and staff were a limitation.

Attaching meeting materials to the agenda, he said, “We can work on that.”

“I think it’s reasonable for those types of presentations to be made available to the public.”

Catherine McLaughlin can be reached at cmclaughlin@cmonitor.com. You can subscribe to her Concord newsletter The City Beat at concordmonitor.com. Reporter Michaela Towfighi contributed to this report.

Baseball: Slow night at the plate costs Concord in loss to Windham, 3-1

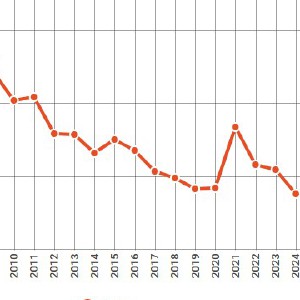

Baseball: Slow night at the plate costs Concord in loss to Windham, 3-1 New Hampshire births fell to a modern low in 2024

New Hampshire births fell to a modern low in 2024