Opinion: Is everything a fluke?

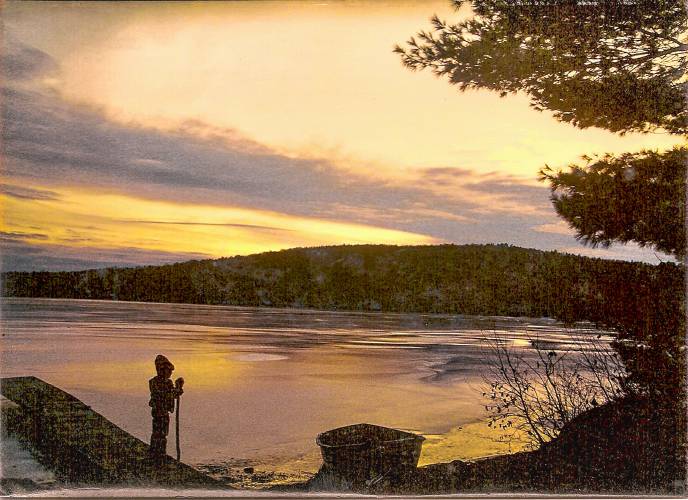

A photo of Stimmell’s son at Jenness Pond near the Solstice 40 years ago. Jean Stimmell photo

| Published: 01-04-2025 6:00 AM |

Jean Stimmell, retired stone mason and psychotherapist, lives in Northwood and blogs at jeanstimmell.blogspot.com.

Humans have always gotten despondent when winter solstice descended, causing the world to go dark. In response, religions of every stripe, Jewish, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, have sprung up to make sense of the impending gloom and promise a return of the light.

Conversely, scientists are like Joe Friday in the old TV detective show. They seek not miracles but “just the facts.’” Pushing this approach to its limit, Brian Klaas has a new book based purely on facts, claiming explanations don’t exist. Everything that happens to us is a fluke.

Klaas’s thesis is based on Chaos Theory, a new science I first discovered in 1987 when reading James Gleick’s best-selling book by the same name. Chaos studies offer a profound new way of seeing order and pattern in what was formerly considered only random, erratic, and unpredictable.

Here’s a famous example from his book. One would assume a butterfly fluttering around in Peking, China, is a perfect definition of randomness. But it’s not. Gleick’s book shows how minuscule actions (like the beating of the butterfly’s wings) can cause far-reaching consequences, like a major storm that slams NYC a few days later. As actor Jeff Goldblum sums it up in Jurassic Park: Chaos “simply deals with unpredictability in complex systems.”

Yes, unpredictability is the coin of the realm!

Nonetheless, forecasters, pundits, and policymakers relying on ever-more sophisticated models have developed a dangerous hubris about their ability to control the world. They are constantly proven wrong but rarely learn the lesson.

When catastrophe comes, people instinctively search for straightforward patterns and clear-cut explanations. “Everything happens for a reason” isn’t just a mantra stitched on pillows; it’s also a flawed assumption underlying social research, including in economics and political science. Unfortunately, it’s not true: Some things … just happen.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Facing 30% budget cut, university leaders say raising tuition is not an option

Facing 30% budget cut, university leaders say raising tuition is not an option

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

A city for coffee lovers: Northeast Coffee Festival returning to Concord this weekend

A city for coffee lovers: Northeast Coffee Festival returning to Concord this weekend

New Hampshire State Police join ICE task force

New Hampshire State Police join ICE task force

25-year-old man shot by police in Keene, AG investigating

25-year-old man shot by police in Keene, AG investigating

A lesser thinker and writer than Klaas might lapse into nihilism. Why bother trying if life is completely out of our control? Not Klaas. He finds in chaos an invigorating elixir of liberation, reassurance, and above all, gratitude.

He believes that a good society is one in which we accept the uncertain and embrace the unknown. “To do so, we must make sure that each of our daily lives is full of exploration, simple pleasures, and pleasant surprises — flukes — and moments where the anxious futures embedded in to-do lists are obliterated in our minds, at least for a time, by a feeling of joy in the present moment.”

As such, his approach sounds similar to the Eastern idea of Karma, the belief that a person’s actions and choices will inevitably shape not only their present life but their future lives (of their descendants).

Today in America, “We’ve engineered a society that is, in too many ways, the opposite of that good society, in which day-to-day life is over-optimized, over-scheduled, and over-planned, while society itself is more prone to unwanted surprises, of catastrophic upheaval and destructive disorder.”

“We’ve invented an upside-down world where Starbucks will remain unchanging, while rivers dry up and democracies collapse. We’d be better off with daily serendipity but stable structures.”

We are like those butterflies, and they are like us, part of a chaotic, networked unity we call existence. “When we try to pick out anything by itself,” the naturalist John Muir once said, “we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

The paradox, then, is that while we control nothing, we influence everything. As chaos theory proves, every action has an unforeseen ripple effect in an intermeshed system. Nothing is meaningless. And that yields a profound truth — that everything we do matters.

Opinion: Protect our winters!

Opinion: Protect our winters!