Beekeepers, farmers square off in NH Senate committee hearing

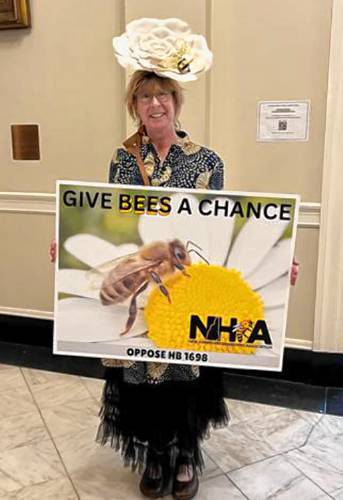

Mary Ellen McKeen, president of the N.H. Beekeepers Association, poses in the State House on Thursday. She testified against a bill that would allow pesticides to be sprayed from drones without notifying neighbors first. Rick Green—The Keene Sentinel

|

Published: 04-19-2024 11:43 AM

Modified: 04-19-2024 2:59 PM |

Farmers and beekeepers seem like natural allies, but they disagreed Thursday on House Bill 1698, which would allow people to spray pesticides from drones without first notifying neighbors.

Mary Ellen McKeen, president of the N.H. Beekeepers Association, came to the N.H. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee meeting with a large replica of a white flower on her head, complete with a simulated honey bee.

She said that if beekeepers are notified before spraying occurs, they can take steps to keep their bees safe, like temporarily closing their hives so they can't fly out.

“The only way we can protect our bees is to sequester them for the time that it takes for the pesticide to become inert, or to move the colonies altogether from the area,” she said. “If bees are allowed to be out foraging while the spraying is happening, it will kill the foragers.”

Bees can also bring pesticides back to their hive and poison their entire colony, and ruin the wax and honey, she said.

In an interview after the meeting, she pointed out that the notification process need not be complicated, and could be done online.

State Agriculture Commissioner Shawn Jasper testified in “strong support” of the bill.

He encouraged open lines of communication between beekeepers and farmers about pesticide application, rather than a notification requirement.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

To provide temporary shelter, Concord foots the bill for hotel stays for people experiencing homelessness

To provide temporary shelter, Concord foots the bill for hotel stays for people experiencing homelessness

‘I’m a whole different kind of mother’ – Raising a four-year-old at age 61 is just life for Barb Higgins

‘I’m a whole different kind of mother’ – Raising a four-year-old at age 61 is just life for Barb Higgins

Authorities believe mother shot three year-year-old son in Pembroke murder-suicide

Authorities believe mother shot three year-year-old son in Pembroke murder-suicide

‘I hate to leave’: Three-alarm fire in Loudon burns centuries-old home to the ground

‘I hate to leave’: Three-alarm fire in Loudon burns centuries-old home to the ground

Hometown Hero: Joan Follansbee energizes morning drop-offs with dance moves

Hometown Hero: Joan Follansbee energizes morning drop-offs with dance moves

Merrimack Valley superintendent Randy Wormald to retire at end of next school year

Merrimack Valley superintendent Randy Wormald to retire at end of next school year

“What I’ve suggested to people is, ‘How about a little cooperation?’ ’’ Jasper said. “You have a hive near a field, talk to the farmer. Let them know your hive is there. Ask them if they’ll notify you if they are going to be spraying. I can’t imagine that there would be a farmer who would say, ‘No, I’m not going to let you know.’ ”

House Bill 1698 would update a state law on the aerial application of pesticide.

When that law was passed in 1995, aerial spraying was done by airplanes and helicopters, not drones. The law requires, among other things, that the state provide written approval for aerial spraying and that neighbors with buildings within 200 feet of the spray area receive prior written notification.

HB 1698 would remove these requirements. It would prohibit the drones from flying higher than 20 feet above the ground.

Farmers testified that drone spraying allows them to target specific areas, using less pesticide and presenting less danger for bees and other pollinators than would be the case if they sprayed pesticide from the ground. There is no notification requirement for ground spraying.

They also said drones don’t fly in high winds, minimizing chances pesticide would drift out of the spray area.

Joseph Mercieri, owner of White Mountain Apiary and Bee Farm in Whitefield, argued against HB 1698. He said the legislation would endanger his 150 hives and his business in general.

He asked whether the state would reimburse beekeepers for hives lost due to aerial pesticide applications done without notification of neighbors.

“We suggest that you consider throttling back on this bill and take another approach,” he said.

Mercieri said a better system should be put in place for registering honey bee farms and notifying them before spraying occurs. One possibility, he said, would be an online map of bee yards that farmers could consult before spraying.

“All we want is to be informed. We want a phone call.”

Sheldon Sawyer, owner of Crescent Farm in Walpole, said he considered drone spraying last year, but rejected the idea as too complicated under current state law.

“One of the problems with notification is I probably have 50 abutters. I believe in the aerial application rules now, you have to send a registered letter. How would you get the addresses?”

The House approved HB 1698 in a voice vote on March 28 and sent it to the Senate. The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee will eventually schedule a vote to make a recommendation on the bill to the full Senate.

Photos: Signs of spring

Photos: Signs of spring 25-year-old Concord man identified as Steeplegate Mall RV fire victim

25-year-old Concord man identified as Steeplegate Mall RV fire victim